Canadians do not have the capacity to effectively police or filter who applies to come, visit, study, work, and live here.

Canada’s immigration system is primarily designed to vet individuals through official documents and data that are crucial for processing applications. However, the system assumes certain global uniformity in how identity and family structures are defined, which is far from reality. In countries with less rigid or vastly different identity tracking systems, policing who comes to Canada becomes a challenge.

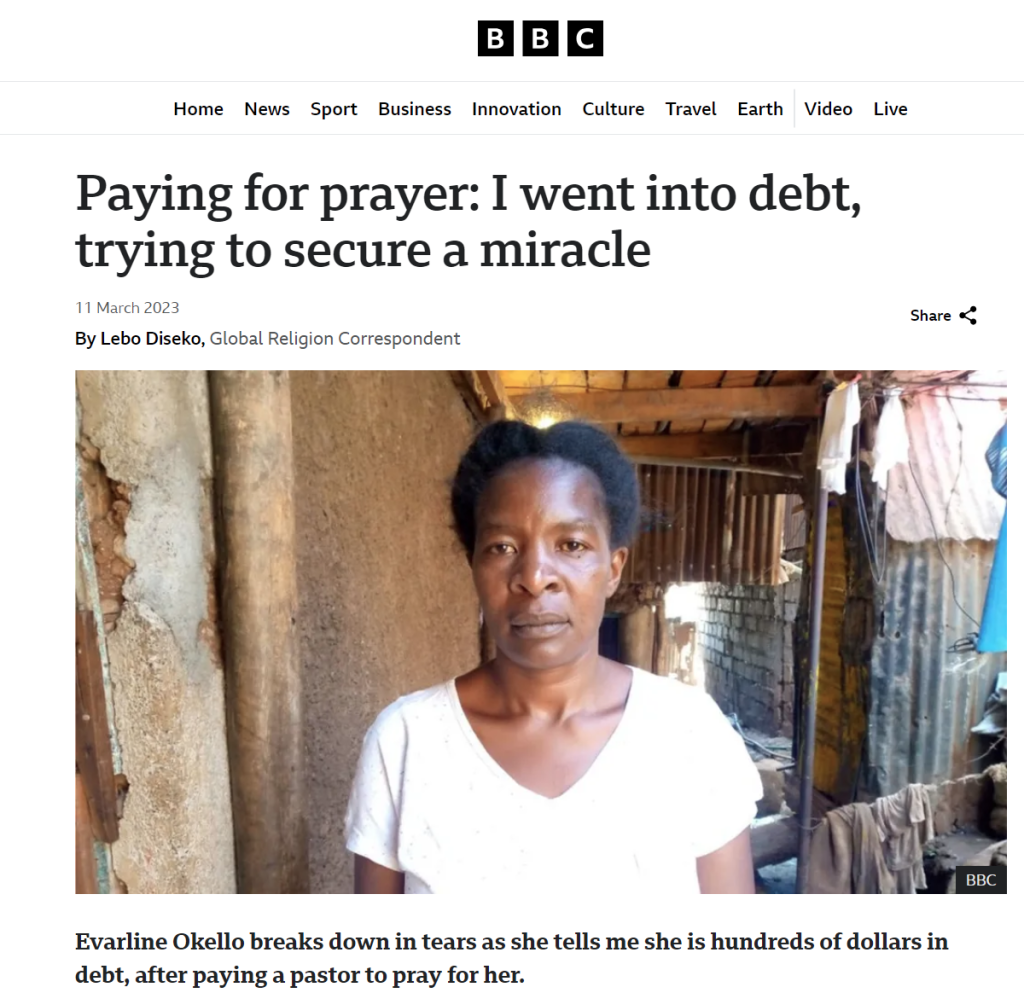

For instance, in many African nations, birth records may not be common, or they might be issued years after birth, making age verification difficult. In such systems, identifying an individual for immigration purposes can be hard, as they may lack formal documents like birth certificates or consistent naming structures. Some migrants might provide different information to fit the application requirements, which could result in identity discrepancies.

Other countries with weaker governance, like parts of India or rural areas in Latin America, face similar challenges. In rural parts of India, it is not unusual for people to have no official records at birth, and names may change as children grow. This mirrors the situation portrayed in Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger, where official identity is fluid and can be easily manipulated. This creates challenges for countries like Canada when verifying an individual’s background.

The Cultural Variability of Guardrails in Society

Society is made up of certain building blocks, each of which has some guardrails. Such unique blocks include individual, immediate family, extended family, clan, etc. Each building block has a guardrail.

In Canada, the foundational building blocks of society are individuals and families, with clear and structured definitions backed by official documentation. An individual in Canada is tied to a birth certificate, a gender marker, a first name, middle name, and last name, and a physical address. This consistent information across all citizens forms the basis for identity verification, making it easier to process and filter who applies to migrate.

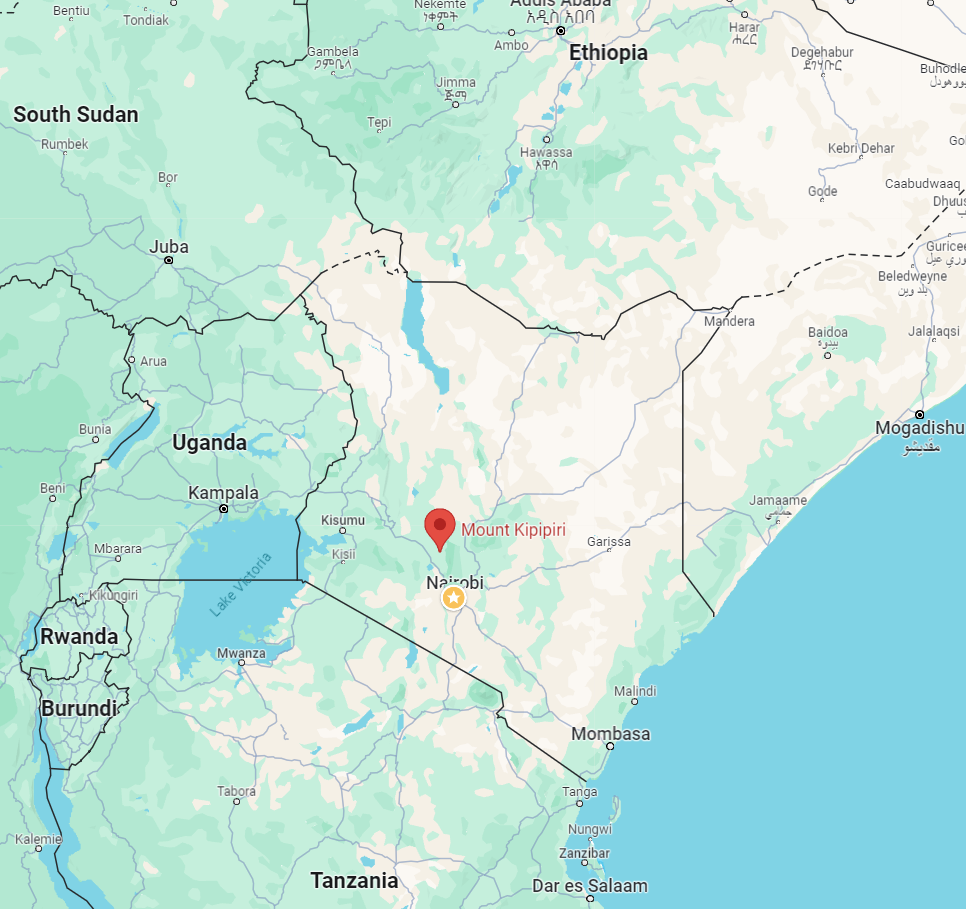

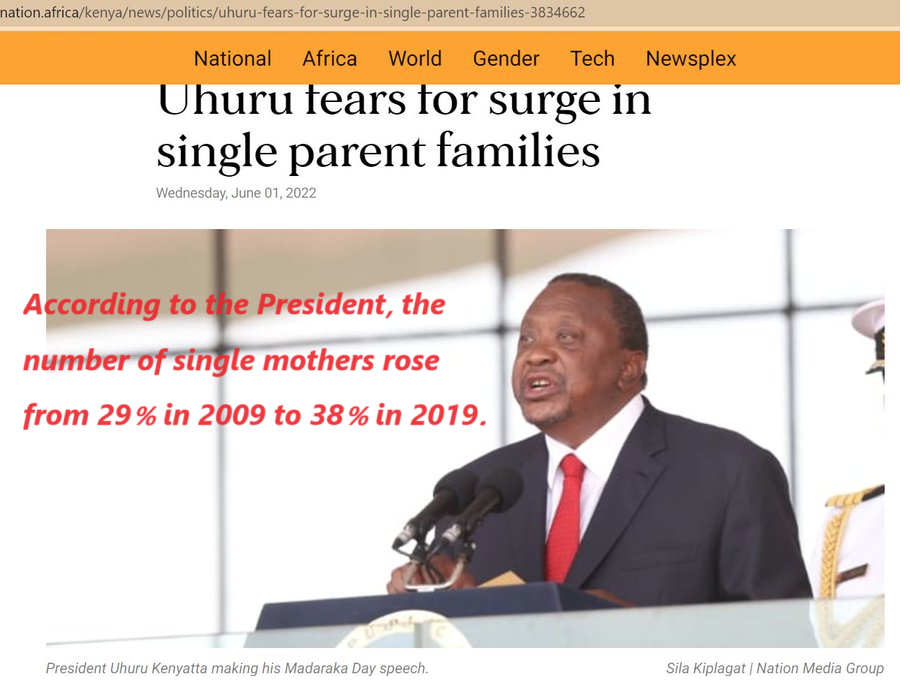

By contrast, many countries do not have such well-established systems. In some African and Southeast Asian nations, identity is tied more to the immediate community or clan, rather than a formal registry of individuals. For instance, in rural communities in Kenya, many individuals may not have formal birth certificates and might only be officially documented when they enter school or formal employment. A child’s identity might change over time with nicknames, further complicating any formal records.

In Somalia, family and clan relations often dominate identity. Clan affiliations are key in defining a person’s status in society. Family records may not exist, and many Somali citizens rely on clan elders or oral histories for documentation, complicating migration processes where formal documentation is required.

Similarly, in many Middle Eastern communities, clan or tribal affiliations can supersede formal national identities. The complexity of large extended families, especially in polygamous cultures, also brings complications when migrating to Western countries. Determining who qualifies as a legal spouse or child can cause administrative headaches when different wives or children from multiple marriages apply together.

The Challenges of Polygamy and Clan-Based Systems in Immigration

When a family is migrating to Canada from communities with polygamous or clan-based systems, some challenges arise.

In many African and Middle Eastern cultures, polygamous families are common, and often, children from all wives are treated equally. When one member of such a family applies for immigration, it can be challenging to identify who counts as an immediate family member. For example, if a man with multiple wives applies to move to Canada, which wife and which children are included in the official documents? What happens to the other wives and their children?

In cultures where family and clan responsibilities transcend nuclear family definitions, identity becomes fluid. In Kenya, for instance, the term “mbari” refers to an extended clan-like structure where all descendants of a common ancestor live in the same locality. Children are often seen as collective assets of the entire family unit. In some cases, it would not be surprising to see one uncle list his nieces and nephews as his own children when migrating, creating confusion during the vetting process.

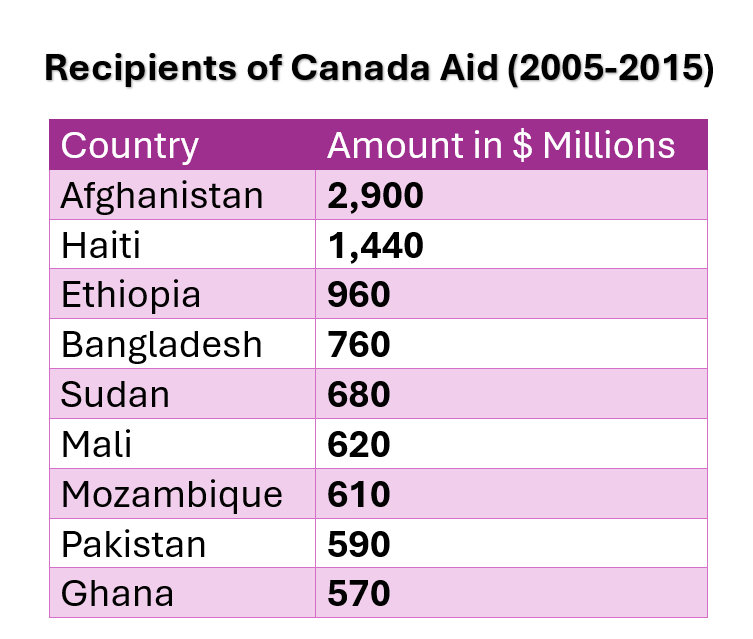

Similar issues arise in rural areas of countries like Afghanistan, where a person’s identity is tied to their tribe or village rather than just their immediate family. These differences complicate Canada’s immigration system, which is based on clear, individual family units.

The challenges posed by immigration systems that assume universal standards of identity reflect the broader issue of cultural diversity in our increasingly globalized world. Each country must adapt to these realities if it hopes to successfully manage immigration.