Overview of International Aid:Dehumanizing Canadians

I remember my first day at school vividly. It was a rainy day, and my father carried me on his shoulders through the downpour. Beyond that, the details blur, but one memory stands out sharply. As we made our way home, I noticed a boy having the time of his life, playing in the freshly deposited silt along the path that led in and out of the school. He made the sounds of a car and kicked mud backward with his feet, imitating a vehicle stuck in the mud. Later, I learned his name was Anthony, and he would become the first person from our elementary school to attend university.

Sometimes I wonder how I made it home that day. My father had left me at school, and I wouldn’t see him again for what felt like an eternity, though I can’t recall if it was months or years later.

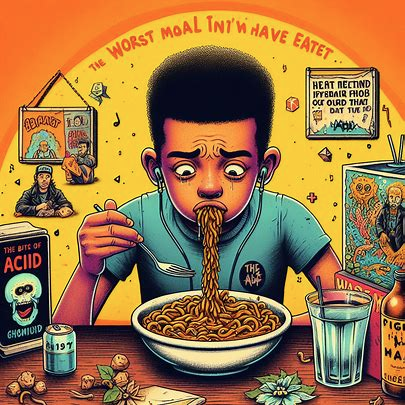

This was 1970, and our school had a free lunch program. The meals were simple: beans and a foreign ingredient called “maakoroni”. We referred to this meal as “thuburo.” While beans were familiar, maakoroni was entirely new to me. The meals were served in aluminum bowls, and they were awful, the worst thing I had ever tasted.

The problem wasn’t just the unfamiliar ingredient. Even if the cook had been taught how to prepare it properly, he lacked the necessary ingredients and methods. The maakoroni was cream-colored and shaped like snail shells. When boiled, it was soft, served cold (there was no other choice), and tasted horrible. Oddly, when raw, it was crunchy and tasted better. Occasionally, the cook’s son would sneak some raw maakoroni from the kitchen and share it with his closest friends, who would pass it down the chain. I was two or three boys away from the son, so I only got a few pieces, and that happened no more than twice.

The beans, though familiar, were dry and required a lot of water and long cooking times to be palatable. But at school, there wasn’t enough water, firewood, or time to cook them thoroughly for hundreds of kids.

The thuburo program lasted for two semesters, about two-thirds of the school year. Toward the end of the second semester, it was announced that starting from the third term, thuburo would be available for a fee. When the third semester came, some kids had paid and continued with the program. My mother couldn’t afford the fee, so I didn’t participate. The program lasted for only one paid semester before dying off due to lack of subscriptions.

Fifty years later, the thuburo program resurfaced in my mind while working in the realm of the “Lords of Poverty.” I came to understand firsthand how such aid programs worked. I realized that maakoroni was our localized name for macaroni, indicating that the aid was from Italy. The fee that cropped up after only two semesters was a factor included in every aid program under the guise of sustainability. For the thuburo program to continue, our parents would have had to import Italian food indefinitely. I have yet to discover the actual name for thuburo, but the lessons it taught me about aid programs and their implementation have stayed with me.

Reflecting on those days, I see how such programs, while well-intentioned, can sometimes miss the mark. They can introduce foreign elements that are hard to integrate into local cultures and fail to consider the long-term sustainability for the communities they aim to help. The thuburo program was a small slice of a much larger picture, a picture that I would come to understand only years later in my professional life. Read: My Descent into Darkness.

Overview of International Aid: Dehumanizing Canadians

International aid, designed to alleviate suffering and foster development in impoverished regions, has been a cornerstone of global humanitarian efforts for decades. However, a critical examination of these initiatives reveals a darker side: the potential dehumanization of both the recipients and the donors, particularly Canadians. Graham Hancock’s seminal work, *Lords of Poverty*, sheds light on the intricate and often troubling dynamics of international aid, raising questions about its efficacy and ethical implications.

The Dual Faces of Dehumanization

Dehumanization is a complex phenomenon that can manifest in subtle and overt ways. It involves stripping individuals or groups of their dignity, reducing them to mere statistics or objects of pity. This dehumanization affects not only those who receive aid but also those who give it, creating a pervasive cycle that undermines the fundamental principles of humanity and compassion.

Dehumanizing the Recipients

In the context of international aid, recipients often find themselves portrayed as helpless and incapable, their identities reduced to images of suffering and destitution. This narrative, perpetuated by fundraising campaigns and media representations, can erode the dignity and self-worth of those in need. The constant depiction of recipients as mere victims fails to recognize their agency, resilience, and potential, perpetuating a one-dimensional view that hinders genuine development and empowerment.

Hancock’s *Lords of Poverty* explores how aid agencies, in their quest for funding, often resort to sensationalizing poverty and suffering. This approach not only distorts reality but also perpetuates a cycle of dependency, where aid becomes a temporary band-aid rather than a catalyst for sustainable change. The dehumanization of recipients, thus, becomes a byproduct of a system more focused on fundraising and self-preservation than on fostering long-term development.

Dehumanizing the Donors

The impact of dehumanization extends to donors as well, particularly those in countries like Canada, where humanitarianism is deeply ingrained in the national consciousness. Canadian donors, motivated by compassion and a desire to help, often find their contributions reduced to mere transactions. This transactional nature of aid can create a disconnect, where donors are seen not as partners in development but as distant benefactors. The emotional and moral engagement that should accompany giving is diminished, reducing the act of giving to a duty rather than a genuine expression of solidarity.

Moreover, the portrayal of aid recipients as faceless masses in need of rescue can foster a sense of superiority among donors. This dynamic can lead to a paternalistic view of aid, where the complexity and capability of those receiving help are overshadowed by the benevolent image of the donor. Such perceptions can erode the mutual respect and equality that should underpin international aid efforts, leading to a form of dehumanization that affects both parties.

The Canadian Context

For Canadians, who often see themselves as global citizens committed to humanitarian values, the implications of dehumanization in international aid are profound. The use of tax dollars to fund aid programs that inadvertently dehumanize both recipients and donors raises ethical and practical concerns. It challenges Canadians to rethink how aid is structured and delivered, urging a move towards approaches that uphold the dignity and agency of all involved.

Rethinking International Aid

Addressing the dehumanization inherent in international aid requires a paradigm shift. It calls for a more holistic and respectful approach to development, one that prioritizes the empowerment and participation of recipients. Aid organizations must move away from sensationalism and towards narratives that highlight resilience, innovation, and partnership.

For donors, including Canadians, this shift means engaging more deeply with the causes they support, fostering a sense of global solidarity rather than distant charity. It involves recognizing the complex realities of those they aim to help and supporting initiatives that promote sustainable and inclusive development.

Conclusion

International aid, while well-intentioned, is fraught with challenges that can lead to the dehumanization of both recipients and donors. Graham Hancock’s *Lords of Poverty* provides a critical lens through which to examine these dynamics, urging a re-evaluation of how aid is conceptualized and implemented. For Canadians, this re-evaluation is not just a moral imperative but a call to action to ensure that their contributions truly uplift and empower, rather than diminish, the humanity of all involved. By embracing a more respectful and participatory approach to international aid, we can move closer to a world where dignity, equality, and mutual respect are at the forefront of humanitarian efforts.