The Dehumanizing Impact of Tax Dollars on Canadians.

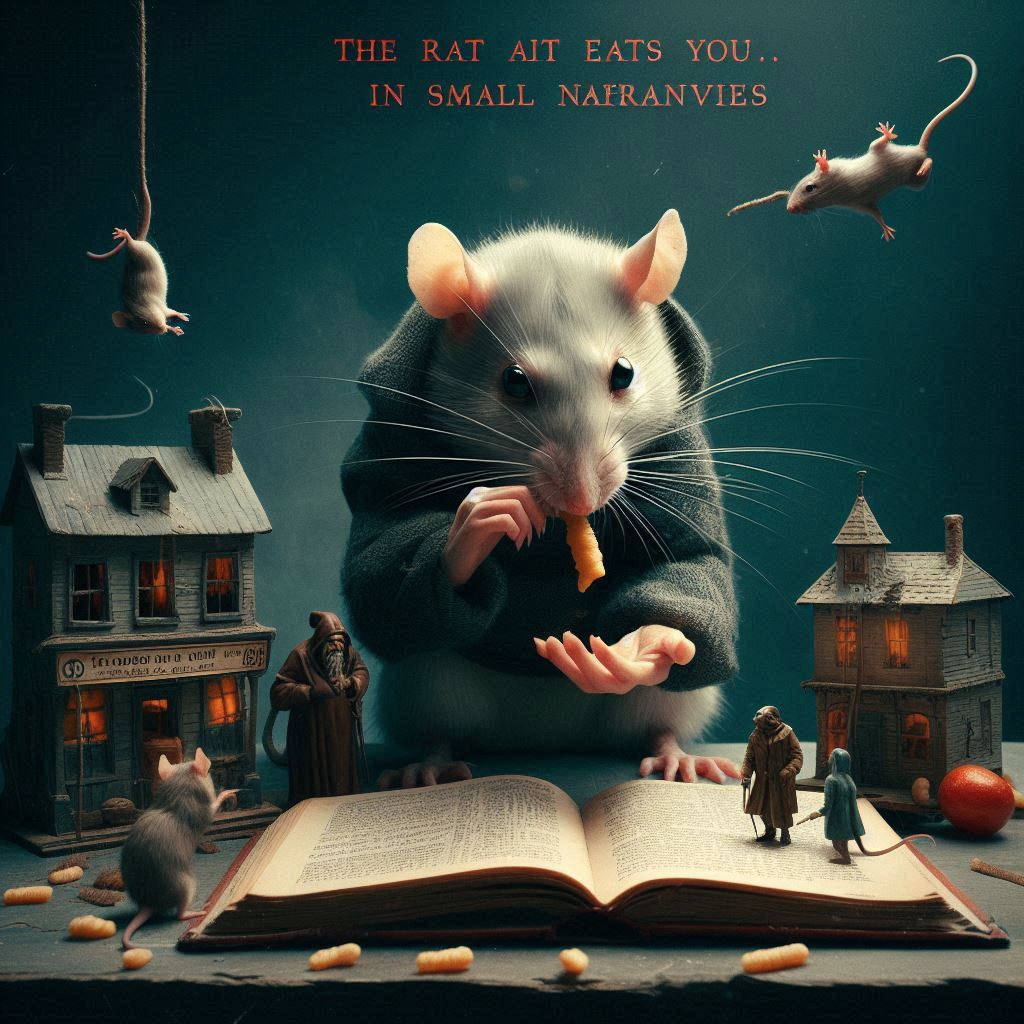

I shared a story my mom talked about how the rat eats you in small bites. My childhood was not anything that many Canadians would identify with, except perhaps as an object of pity.

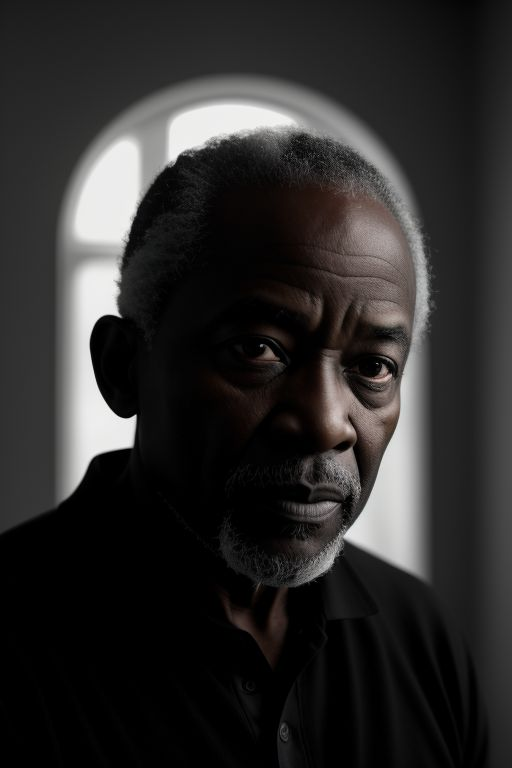

When I was young, my mom set a clear path for me to follow, and I diligently met every target along the way. This determination continued throughout my working life, even after I arrived in Canada as a skilled immigrant. I came with confidence, ready to find work in my field and make a positive contribution to my new home and family. I had always achieved what I set out to do.

The change crept on me slowly. I remember clearly when I learned that I was poor. The speaker was good at what they did. He gave an analogy, saying “If all you have known in life is hunger, then you would know that you are hungry. Poor people don’t know that they are poor,” he concluded. That moment was my Saul-like revelation. From then on, slowly, subtly but surely my life turned for the worse. I endured the most deep and targeted abuse at that place beyond anything I ever imagined. By the time I quit, I was emotionally and psychologically broken. It took me more than five years, even with professional help, to begin to muster the courage to step into the world again with confidence. I am still working on it.

I share this personal experience to highlight how the use of tax dollars can sometimes inadvertently dehumanize Canadians.

Dehumanizing Canadians: Impact on Society

Dehumanization is a multifaceted and widespread occurrence that carries significant consequences for individuals, groups, and entire societies on a global scale. Within the realm of international aid, it takes on diverse manifestations, influencing both those who provide assistance, such as donors, and those who are meant to receive it, namely aid recipients. In this examination, I intend to delve into the societal repercussions of dehumanization, with specific attention to its effects on Canadian donors and individuals in Canada who bear resemblances to aid beneficiaries.

Health

Health disparities are a glaring consequence of dehumanization. In “Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Healthcare,” Dayna Bowen Matthew highlights how systemic biases in healthcare lead to poorer outcomes for marginalized groups. Similarly, in Canada, donors and those depicted in aid campaigns often receive inadequate healthcare due to stereotypes that they are either too privileged to need help or too dependent on charity. These perceptions can result in a lack of empathy from healthcare providers, leading to disparities in treatment and outcomes. This echoes Khiara M. Bridges’ arguments in “Critical Race Theory: A Primer,” where systemic inequities in healthcare are perpetuated by dehumanizing ideologies.

The psychological toll of being dehumanized in healthcare settings cannot be understated. Professor Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking, Fast and Slow” explains how cognitive biases, such as stereotyping, influence our judgments and actions unconsciously. When healthcare providers hold biased views about these patients, it can hinder their willingness to provide thorough and compassionate care, exacerbating health disparities.

Education

Educational opportunities are also affected by dehumanization. Children from families involved in aid work or those represented in fundraising imagery may be stigmatized in educational settings. This can lead to lower expectations from educators and peers, impacting their academic performance and self-esteem. These children might internalize negative stereotypes, leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy of underachievement. Daniel Kahneman’s insights into cognitive biases highlight how these prejudices can affect educators’ perceptions and actions, further disadvantaging these students.

Moreover, the psychological perspectives on poverty, as discussed by Ben Fell and Miles Hewstone, indicate that poverty can lead to social exclusion and diminished self-worth. This psychological burden is particularly heavy on children, who may struggle to see the value in education if they feel perpetually marginalized. Tracy Shildrick and Jessica Rucell’s sociological perspectives on poverty also emphasize how societal structures and perceptions can perpetuate educational inequalities, reinforcing a cycle of poverty.

Employment

In the employment sector, dehumanization manifests through hiring biases and workplace discrimination. Individuals who are perceived as mere symbols of charity may be seen as lacking self-sufficiency or capability. Graham Hancock’s “Lords of Poverty” discusses how aid can create perceptions of dependency and inferiority. This stigma can follow individuals into the job market, where they may face skepticism about their abilities and motivations. Such biases can result in fewer job opportunities, lower wages, and limited career advancement, perpetuating cycles of poverty and marginalization.

Philip Davis and Miguel Sanchez-Martinez’s economic theories of poverty highlight how economic structures and labor market dynamics can perpetuate inequality. When dehumanized individuals are systematically marginalized in the job market, it not only affects their personal economic stability but also contributes to broader economic inefficiencies and social stratification. The psychological impact of this dehumanization, as discussed by Ben Fell and Miles Hewstone, can lead to decreased motivation and job performance, further entrenching these individuals in poverty.

Housing

Housing is another area where dehumanization has severe impacts. Those who are stereotyped as dependent on aid may struggle to find adequate housing due to prejudices held by landlords and housing authorities. This is exacerbated by the psychological effects of poverty, as discussed by Ben Fell and Miles Hewstone. They note that poverty can lead to social exclusion and internalized stigma, making it even harder for individuals to advocate for their housing needs. Dehumanized individuals may face discrimination in the housing market, leading to substandard living conditions and housing instability.

The sociological perspectives on poverty provided by Tracy Shildrick and Jessica Rucell further explain how systemic barriers and social prejudices contribute to housing insecurity. When people are dehumanized and reduced to symbols of charity or dependency, they are less likely to be viewed as deserving of safe and stable housing. This not only affects their quality of life but also perpetuates a cycle of poverty and marginalization.

Conclusion

The dehumanization of Canadians, particularly those who donate to aid agencies and those depicted in fundraising media, has far-reaching implications across health, education, employment, and housing. By reducing these individuals to mere symbols of charity, society perpetuates stereotypes and biases that hinder their full participation and contribution. As Khiara M. Bridges and Dayna Bowen Matthew highlight, addressing these systemic issues requires a fundamental shift in how we perceive and treat marginalized groups. Understanding the cognitive biases explained by Daniel Kahneman, and recognizing the psychological impacts of poverty discussed by Ben Fell and Miles Hewstone, can help foster more inclusive and equitable policies. It is crucial to move beyond dehumanizing narratives and work towards a society that values and supports all its members.