Tattered Uniforms, Boundless Dream

On a rainy January day, my father dropped me off to start elementary school, a moment etched in my memory. Clad in a school uniform of tailor-made khaki shorts and shirt, the pocket adorned with blue and white strips of dress material, I stood among my peers. The girls wore dark blue sleeveless dresses over white blouses. Some kids could not afford the school uniforms but came to school anyway. Occasionally those without uniforms would be expelled from class and school. The parents would show up at school and made an agreement with the headmaster and agree on plan to provide the uniform. Often this involved buying one piece at time, over a period of several months. Shoes were a luxury, worn only by a few teachers’ children, while most of us navigated the school grounds barefoot. Yet, in our eyes, we were not poor, far from it.

Stitching Stories of Resilience

By the third year, my uniform, particularly the shirt, was a patchwork quilt of repairs. Even the patches began to fray, but this was our norm. We didn’t see ourselves as destitute, deserving pity from the so-called “misery merchants.” We faced problems, but we tackled them head-on, parents and children alike.

Most adults had at least one cherished pair of nice clothing, and those who didn’t were working tirelessly, hearts set on acquiring one. There were two choices when it came to buying clothing: “cia gucururia” (off-the-hanger) and custom-made.

Cia gucururia were the new ready-made clothes. They were considered cheap and less desired, a last resort. The coveted item was simply called “Jinja,” a name referring to a brand of cloth materials produced in Uganda. To acquire a Jinja, you would visit the tailor shop. From the rolls of fabric on the shelves, you’d select your preferred material. The tailor would then unfurl the roll and place it on the counter. Notebook in hand, he’d jot down your name and date, pulling a pencil from behind his ear. With a tape measure draped around his neck, he’d measure your size, constantly seeking your opinion. “Is it too tight? Too loose? Too short? Too long?” He meticulously recorded every detail in his notebook. After some quick calculations, he’d cut the required length of cloth from the choice roll of material previously placed on the counter

The cut piece would then be carefully folded. The tailor would slice a piece of brown paper tape from a roll on a special wooden holder. The tape would pass through a small well of water to activate the glue. When the well was dry, the tailor would lick the tape. The prepared tape would then be affixed to the cloth, your name written on it, and placed on the counter for pending work.

The tailor would return to his station behind the counter, and you’d pay a portion of the agreed price. No one ever had the full amount upfront. It often took several months before the tailor could even begin working on your clothing. The tailor would then return to his workplace behind the iconic Singer sewing machine, a symbol of craftsmanship and dedication.

Journey to the Mission Center: Hope in the Gray

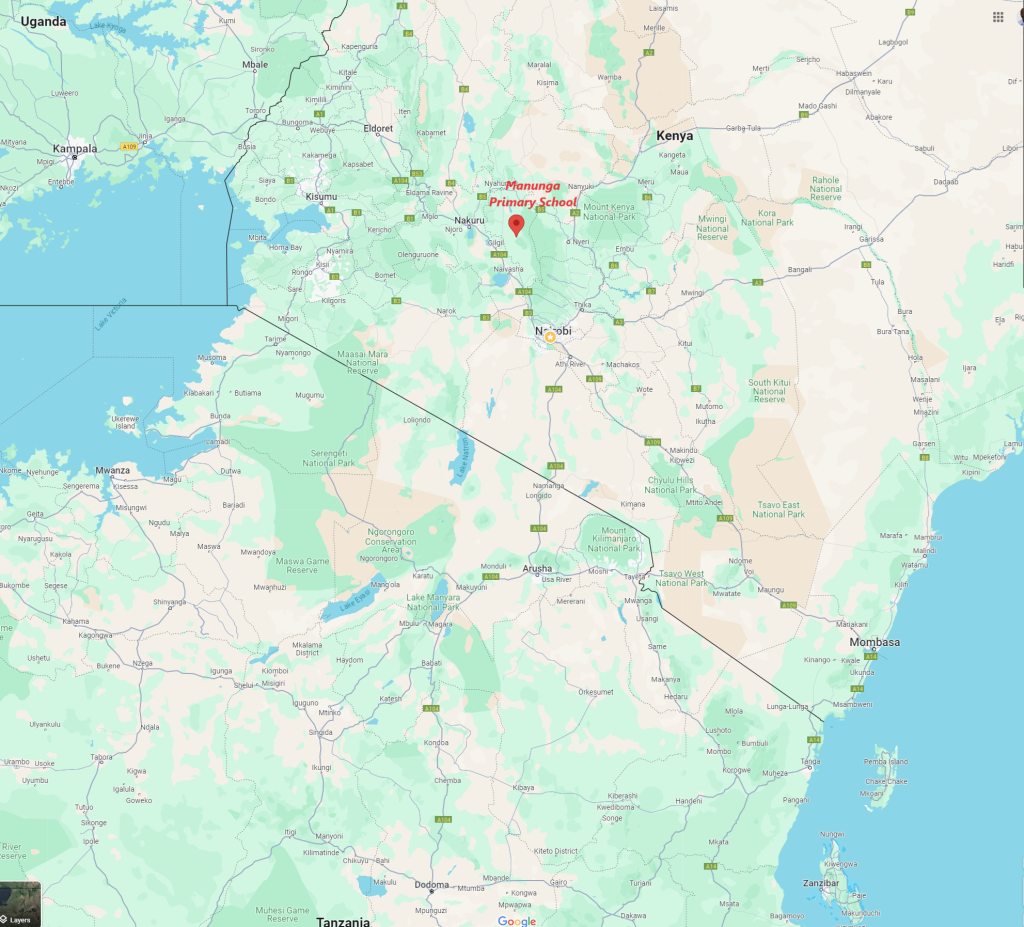

Life took an unexpected turn when whispers spread about free clothing from the Catholic Church, but only for its members. As Presbyterians, my family, and our Seventh Day Adventist neighbors, the Miringas, were excluded. However, my mother and Mama Miringa decided to try the and get the free clothes. Kinyanjui (Miringa’s son) and me were sent to the mission center to beg for clothes.

But one day, my mom and Mama Miringa decided to roll the dice. They sent Kinyanjui (Mama Miringa’s son) and me to the mission center to ask for clothes. The place was immaculate, one of the few spots adorned with all-grey brick houses, each impeccably maintained. The path from the main road was surfaced with compacted quarry stones, a testament to order and care.

As you entered, the church building stood on the right. This same building had doubled as my kindergarten classroom for a brief stint. It was U-shaped, with a long veranda covering the open part of the ‘U’, supported by a hue of blue painted round metal pipes. The residence consisted of two large, round buildings connected by a covered walkway. An outdoor garage at the back could hold several vehicles. The residence was powered by an electric generator. The entrances to the residences boasted large wooden doors that opened into an open-roof courtyard adorned with beautiful flowers. This garden was the stuff of legends, a place few locals ever ventured beyond those big doors. Especially the men’s side, which lay to the left as you approached the compound.

Yet, there were whispers of one young girl who did pass through those doors. She became pregnant and bore a child with skin unlike any of us. There were no albinos in our community, and besides, she was a choir girl who spent a lot of time helping at the church. Her dream, like many other kids, was to become a “sister” or nun. And then, just before the child was born, the local priest, Father Kabinato, vanished without a trace. The rumor mill buzzed with speculation that he was the father of the mzungu child born in the village.

Beyond the Gates: A Tale of Begging and Disappointment

I can’t recall how long it took before we returned, as I couldn’t read or write to mark the time frame. We repeated the knocking and waiting routine. This time, she gave us handkerchiefs, one each. They looked, smelled, and felt nice. We returned home, clutching our small treasures with a mixture of disappointment and newfound hope.

From Handkerchiefs to Hope: Beggar’s Journey

I can’t recall how long it took before we returned, as I couldn’t read or write to mark the time frame. We repeated the knocking and waiting routine. This time, she gave us handkerchiefs, one each. They looked, smelled, and felt nice. We returned home, clutching our small treasures with a mixture of disappointment and newfound hope.

Legacy of Dependency: The Church’s Unintended Impact

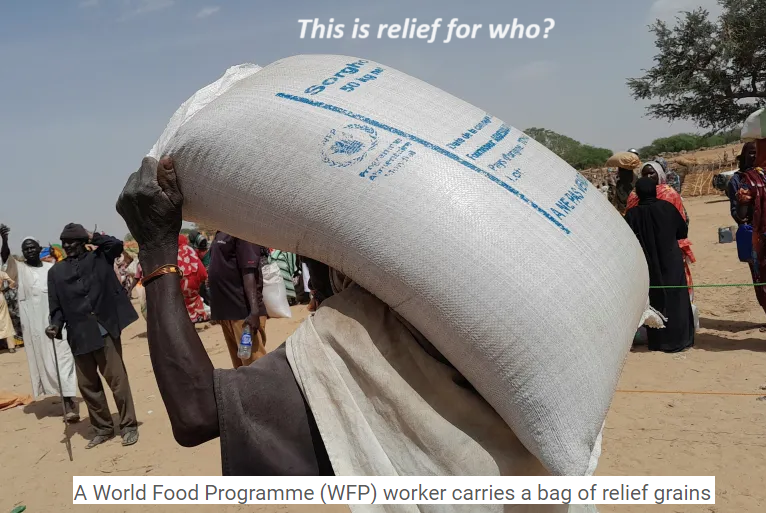

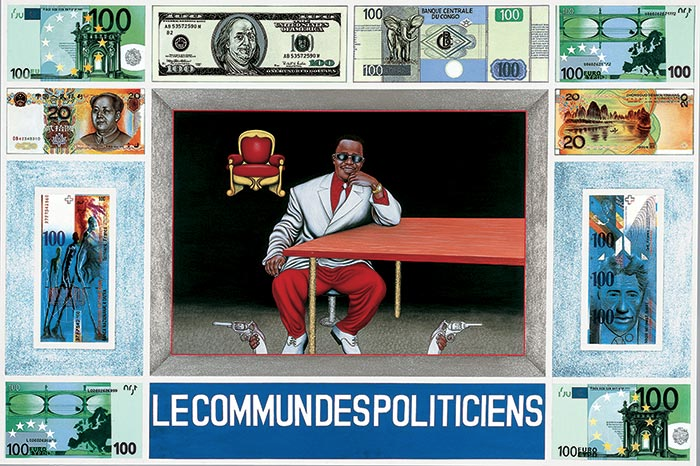

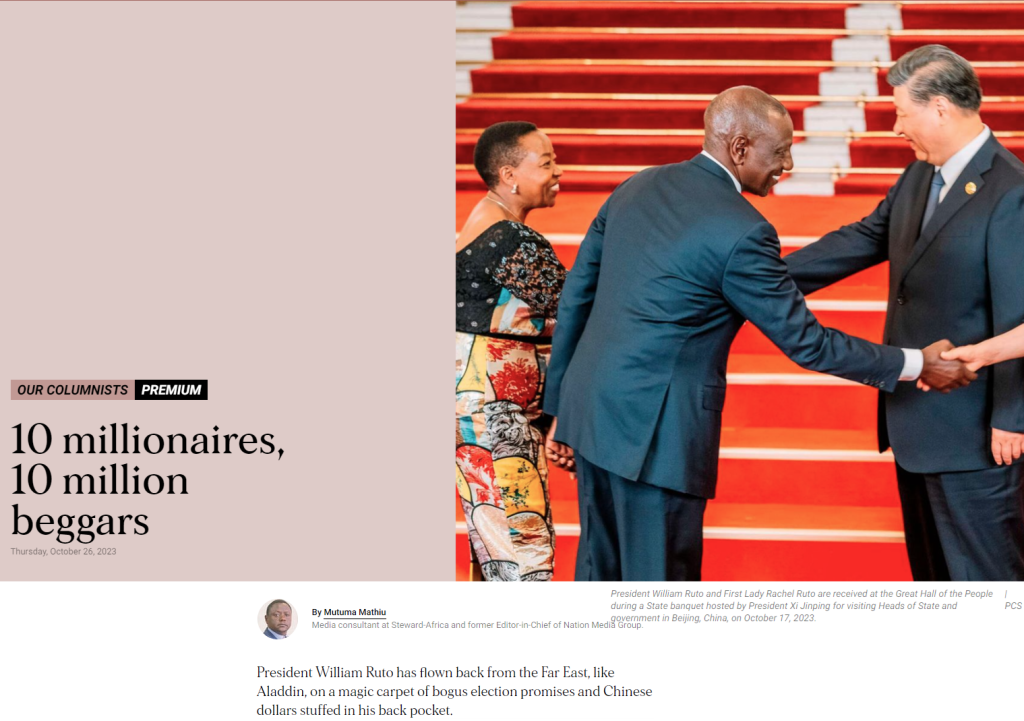

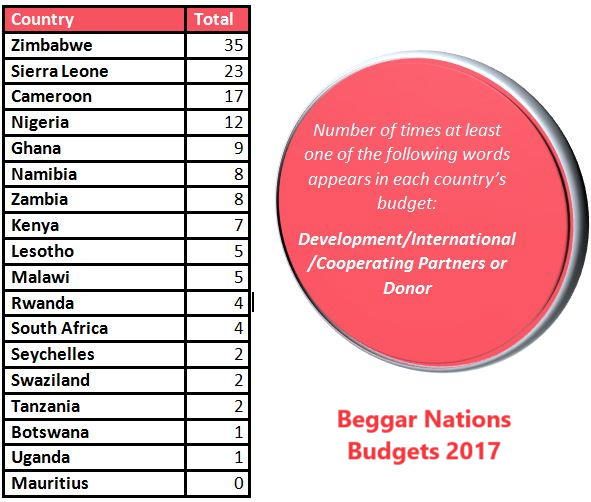

The Catholic Church’s distribution of used clothes fostered a culture of begging and dependency, a legacy that endures today. This well-intentioned charity bred a self-perpetuating beggar nation, exploited by misery merchants seeking tax dollars. Each year, African governments rely on donor money from Western taxpayers, funds often squandered on extravagant luxuries rather than addressing systemic issues.

Despite this backdrop, our spirit remained unbroken. We didn’t see ourselves as victims but as resilient individuals striving for a brighter future. Our struggles were real, but so was our resolve to overcome them. In the garden of misery, we planted seeds of hope, nurturing them with an unwavering belief in our ability to rise above our circumstances. We were not just surviving; we were fighting, dreaming, and building a better tomorrow with every ounce of strength we had.

However, the misery merchants and the lords of poverty, fueled and funded by Western taxpayers, seem determined to keep us dependent. They want to keep us chained to a narrative of need, but we are more than their stories of woe. We are warriors of hope, refusing to be mere pawns in their game. In our hearts, we know that we are destined for greatness, and no amount of external pressure and deceit will dim the fire of resilience burning within us.

Conclusion

To the Lords of Poverty and Misery Merchants, a beggar nation is the proverbial gift that keeps on giving tax dollars, reincarnate.