Twenty-one years ago, my family embarked on a journey across three continents, leaving behind everything we owned to start a new life in Canada as skilled immigrants. Little did we know that the path ahead would be long and arduous, marked by unexpected challenges and unfamiliar experiences.

Upon landing in Canada, we were thrust into a new reality, where even the simplest tasks felt daunting. Basic necessities like kitchen salt seemed elusive, and the familiar comforts of our past life were replaced by uncertainty and confusion. Amidst this upheaval, one aspect of Canadian life stood out to me: the perspective on poverty and donors.

The Perception Gap

Growing up in Kenya, I was accustomed to a different narrative surrounding poverty and generosity. In my community, the notion that a donor from Western countries would arrive and give substantial amounts of money had taken hold. However, my perception shifted upon witnessing the Canadian perspective firsthand.

Donors in Canada were not wealthy magnates or celebrities; they were ordinary individuals—low-paid workers, farmers, and even those on welfare. These generous donors were willing to share what little they had with those less fortunate in Africa. Their empathy transcended borders and economic disparities.

The Deceptive Dollar

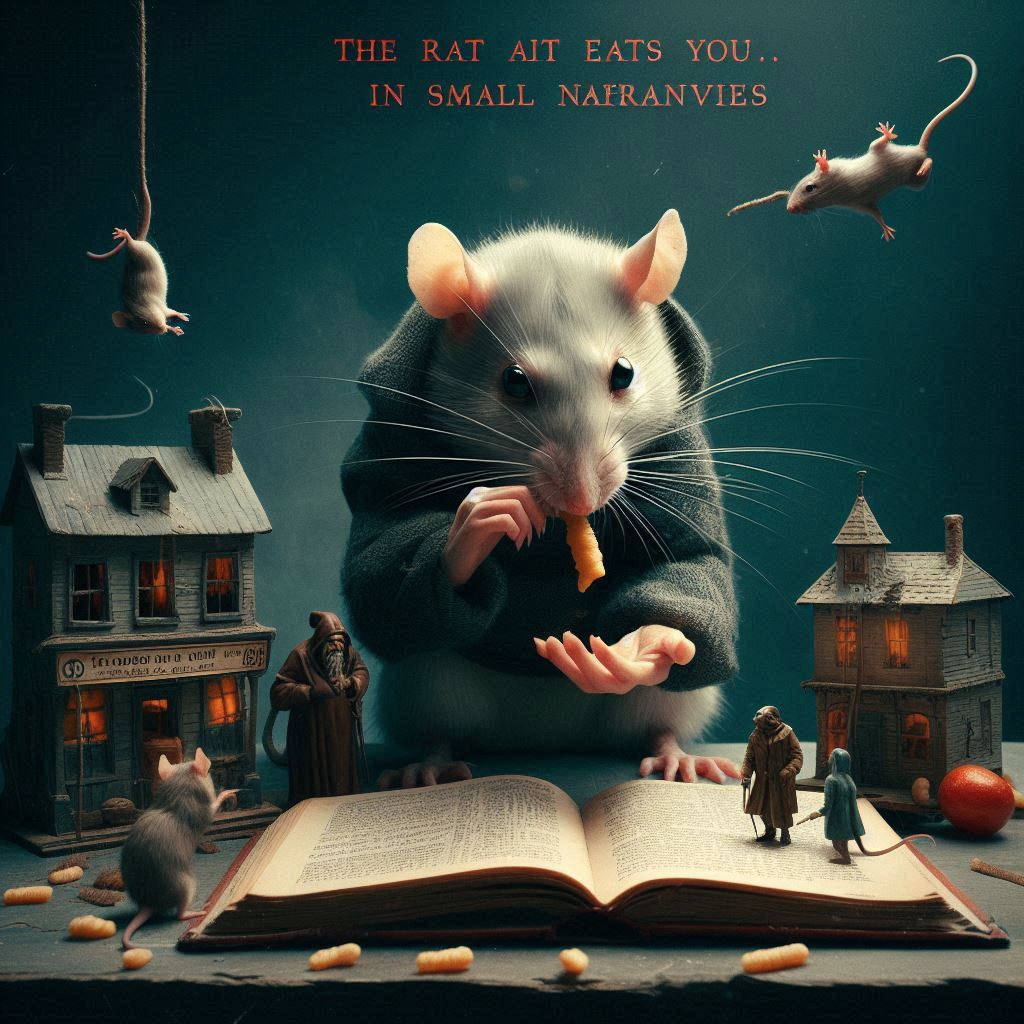

During my tenure with an organization that solicits donations from generous Canadians, I gained valuable insights into the dynamics of international aid. But before delving into these donor insights, let me share a childhood story—a tale of the rat that eats you in small bites.

During my childhood, my brother and I shared a bed, where bed wetting and dust accumulation were common occurrences. Despite my mother’s desperate attempts to instill cleanliness, our bed became a muddy pool of dust and urine, attracting maggots during the cold, rainy months. In a desperate bid to enforce hygiene, my mother resorted to a chilling tale: if we failed to wash our feet before bed, a rat would painlessly nibble at us while we slept, leaving no trace until morning when we would wake up with a gaping hole.

This story of the rat and my childhood perfectly parallels the tactics employed by what I refer to as “misery merchants”—organizations that capitalize on false narratives to solicit donations from Western taxpayers. These merchants peddle the notion that a mere $1 a day can lift an African out of poverty, leveraging shocking images and manipulated stories to tug at heartstrings and open wallets.

However, the $1 figure is a fabrication designed to deceive well-meaning donors. Having lived both in Kenya and Canada, I know firsthand that the aspirations and needs of individuals in both countries are strikingly similar. Moreover, the cost of living in cities like Nairobi and Mississauga is comparable, debunking the notion that $1 holds more value in Africa. $1 is the rat bite, small enough that donors do not feel the pinch.

The Fish and the Bait

To maintain the flow of donations, misery merchants scour the African continent for sensationalized images of poverty, presenting everyday activities as dire circumstances that can be alleviated with a small donation. These visuals prey on the goodwill of donors, perpetuating harmful stereotypes and reinforcing a narrative of helplessness and dependency.

Why Africa? Because the $1 is merely a bait. The real fish they are after are tax dollars, and if Africans are the intended beneficiaries, the fish can be up to ten times bigger.

Dehumanization Effects

This deceptive narrative has far-reaching consequences:

Donors

The media used in fundraising has the potential to instill cognitive biases in donors:

- Anchoring: The initial $1 figure becomes the reference point, skewing perceptions.

- Availability Heuristic: Shocking images create an emotional bias, leading to impulsive giving.

- Confirmation Bias: Donors seek information that confirms their existing beliefs.

- Halo Effect: Generosity attributed to donors overshadows other aspects of their lives.

Black People: The consequence is that black individuals are inherently perceived as deserving of less.

- Education: Black children in school often lack the guidance they deserve. They are unfairly seen as products of their parents and environment, incapable of rearing well-adjusted children.

- Healthcare: Disparities persist, affecting access and outcomes.

- Employment and Job Progress: Stereotypes hinder career growth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it’s crucial to confront false narratives and scrutinize aid initiatives with discerning eyes. While the rat may nibble, we must not be deceived by its seemingly insignificant bites.